Ahh, but predictions are–tonight it will storm. And I just got my basement almost dry — not fully, because the water table languishing under this house must be above its abilities to drink what has been given it for its thirst, and is having to share it with my house foundation. I am grateful it is not a flood here. I am also grateful it is not a dustbowl.

I have been reading Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer. Reading it I am again reminded of the bane of individual land ownership on the health and well being of all beings–those who grow in place such as trees, and grasses, and all flora, those who by creation roam a terrain or airrain (such a word?) or waterrain (such a word?), and those who are us–what if no one owned, and everyone shared? If no one owned, would there be such drive to protect? Would there be a reason for greed?

A world without greed. How beautiful.

And respect. This from the book stays with me: “Someone (in a class learning the Potawatomi language) asks: ‘How do you say please pass the salt?’ Our teacher…. explains that while there are several words for thank you, there is no word for please. Food was meant to be shared, no added politeness needed; it was simply a cultural given that one was asking respectfully.”

Assuming respect. So often I see enacted, and undoubtedly enact myself, an assumption of disrespect from someone else, and gear up for it. And how does one gear up for disrespect? Either defensively or offensively–in each case with tension and distrust. How is that we live in such an uncomfortable state as our very way of life?

Notice the bark of this beech. It is pocked. It is likely enduring bark blight, which has been damaging many beeches, a major tree in the US Northeast. Bad enough, but now! Now the beeches are being attacked by a leaf disease that is rapidly decimating them! The tree here is enduring it now. This particular tree was not affected last year.

“Historically, a blight called beech bark disease has been the primary threat to the species. But now, beech leaf disease appears to pose a bigger danger. First spotted in northeastern Ohio, it causes parts of leaves to turn leathery and branches to wither. The blight can kill a mature tree within 6 to 10 years. It has now been documented in eight U.S. states and in Canada.” [from the journal Science, on line edition, 10 November 2021]

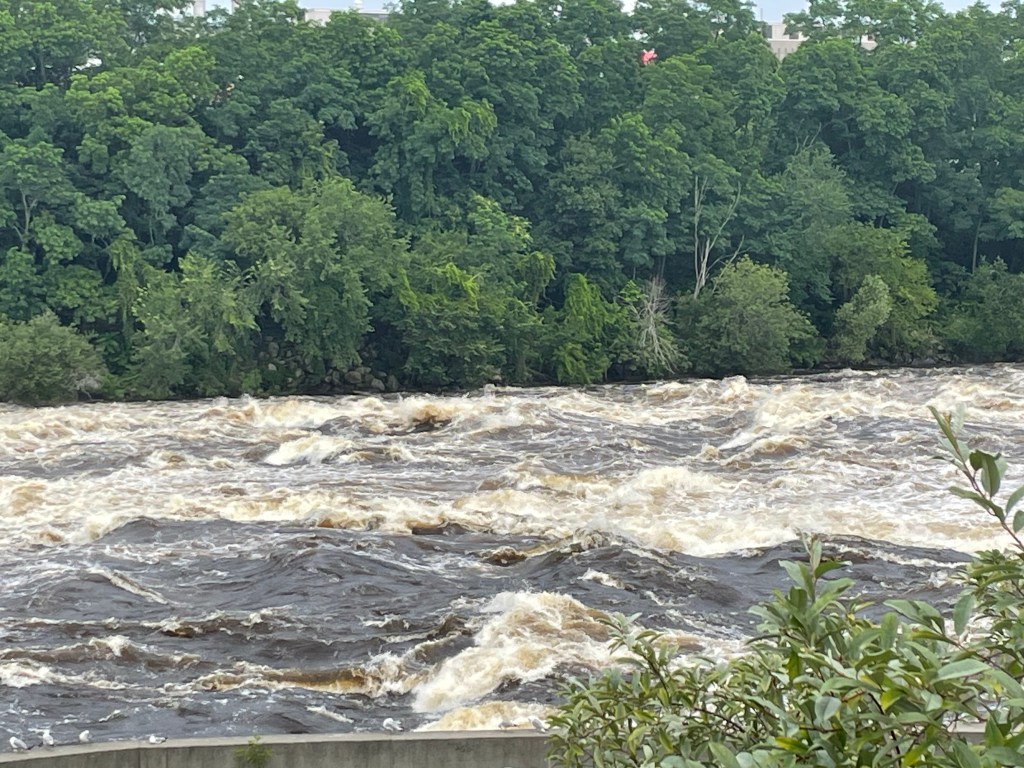

I will go to one more topic. The might Mo — the Merrimack River. She is a caged being, shackled here and there by dams, canals, purification plants (to undo what we discard) and yet she rules.

I have seen the Merrimack River higher, seen it breach its banks, but I have never seen it so much of a force. This was after the rains in mid-July that wreaked havoc upriver and in Vermont and western New Hampshire.

There is much to be concerned about. But there is beauty and through it there is hope.

Your 2nd paragraph reminded me of a talk I heard (or a paper I read) in 1968. It was titled The Tragedy of the Commons. The printed version is here: https://www.asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/1969/JASA9-69Hardin.html. The idea is : “The tragedy of the commons develops in this way. Picture a pasture open to all. It is to be expected that each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons. Such an arrangement may work reasonably satisfactorily for centuries because tribal wars, poaching, and disease keep the numbers of both man and beast well below the carrying capacity of the land. Finally, however, comes the day of reckoning, that is, the day when the long-desired goal of social stability becomes a reality. At this point, the inherent logic of the commons remorselessly generates tragedy.”

LikeLike

Bill, thank you for this. So many thoughts stirred up reading it, and the second article. And wonder.

LikeLike